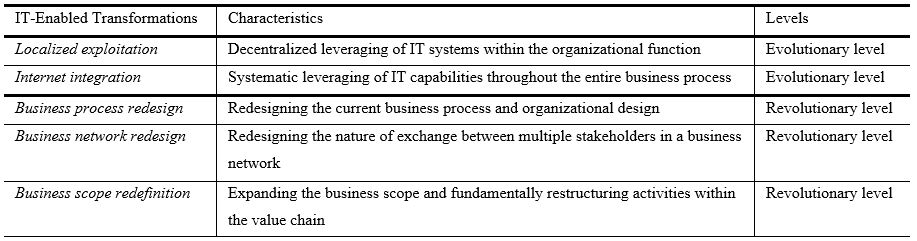

Digitalization started already in the 1960s with the introduction of mainframe computers, followed in the 1980s with the personal computers and the internet in the 1990s (Schwab 2016). Venkatraman described in 1994 five levels of IT enabled Business Transformation, cf. Figure 12 (Venkatraman 1994, 85), summarized by (Ismael, Khater and Zaki 2017, 10) in Table 2.

Porter said already in 1985 “The information revolution is sweeping through our economy” (Porter and Millar 1985) when he was describing how this gives us a competitive advantage. More than 30 years later we might think that this is obvious, but in the 1980s the decision makers struggled with the introduction of information technologies. In 2001 Porter argued that not the internet is changing everything, but it is an enabling technology “a powerful set of tools that can be used wisely or unwisely, in almost every industry and as part of almost any strategy” (Porter 2001, 64). Not the newest technology like by that time the internet gives us a competitive advantage, but it “provides better opportunities for companies to establish distinctive strategic positioning than did previous generations of information technology”. Therefor the question is not whether to deploy a new and possible disruptive technology as according to Porter companies have anyway no choice if they want to stay competitive, but how to deploy it. He formulated 6 principles of strategic positioning (Porter 2001, 71):

- Start with the right goal: long-term return on investment

- Deliver a value proposition different from the competitors

- Have a distinctive value chain

- Robust strategies involve trade-offs (sacrifice existing ways of competing)

- Define how all elements of the value chain fit together

- Continuity of direction

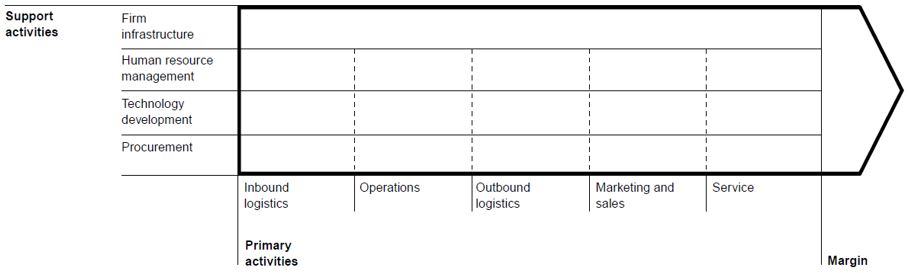

Porter’s approach is – like Venkatraman (1994) calls it – revolutionary and focusses on business process (end-to-end value chain processes) redesign and business scope (value proposition) redefinition. For Porter the value chain gives the dimensions of strategic importance with the nine generic main processes inside a company: (1) firm infrastructure, (2) human resource management, (3) technology development, (4) procurement, (5) inbound logistics, (6) outbound logistics, (7) marketing & sales, (8), service.

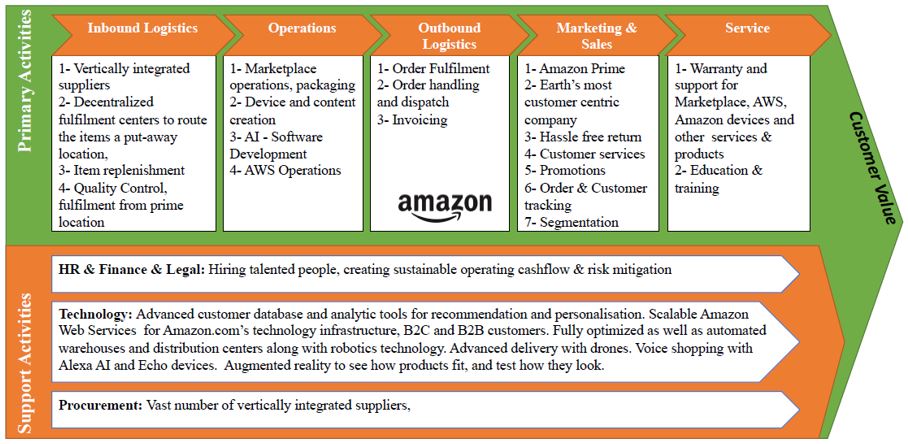

As an example, Kandermirli (2018) describes the digital strategy of Amazon.com using Porter’s value chain model, cf. Figure 20.

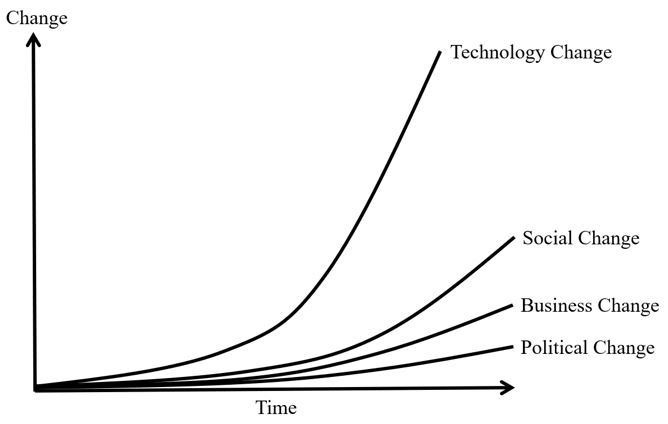

Today new technologies are developing exponentially. This creates a disruptive gap which effects not only the global economy, but also societies, and now determines the fourth industrial revolution (Schwab 2016). This gap is described by Downs and Mui (1998) as the “law of disruption”, because “social, political, and economic systems change incrementally, but technology is changing exponentially” leaving an opening which will be closed either by the next generations or by todays organizations which need to learn from them.

To overcome the “Innovator´s Dilemma” of incumbent businesses in terms of disruptive innovations (Christensen 1997), McKinsey has introduced the three horizon model, featured in the book “The Alchemy of Growth” (Baghai, et al. 1999). This framework provides companies the opportunity for growth coming from future technologies without neglecting the present. The first is a horizon of 3-12 months, focusing on improving performance to maximize the remaining value. The second is a 24-36 months horizon to extend the existing business models and competencies to new opportunities. The third is 36-72 months horizon for the development of new capabilities to prevent disruption. Blank (2019) argues this does not longer apply today as start-up’s are not burdened with any legacy and can develop horizon three as fast as existing businesses deal with horizon one due to declining costs of creation, information and experimentation (Downes and Nunes 2014). Downes and Nunes (2014) say that the most important strategic dimension are leadership skills, it demands courage.

Threats are coming from the market with better and cheaper products and services, some of them will not be recognized until it is too late to counteract. And threats are coming from the inside as organizations are naturally resistant against any kind of change.

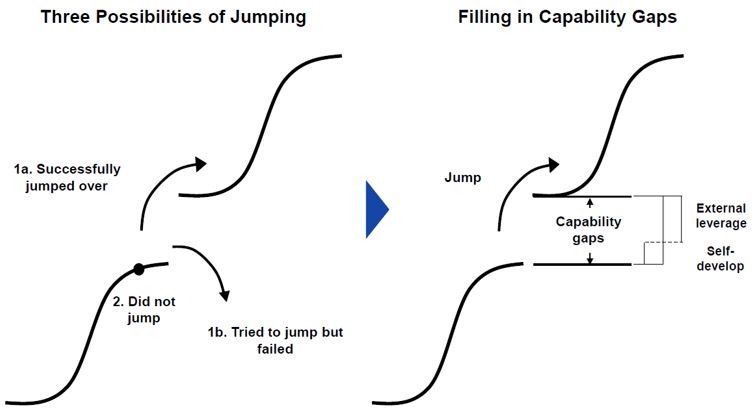

Nunes and Breene (2011) argue that sooner or later companies are at the stage of maturity of the S-Curve (cf. Christensen 1992). Now they have three possibilities: (1) they successfully jump from one business to the next by reinventing themselves, (2) they try to jump, but fail, e.g. because they waited too long with their decision, or (3) they decide not to jump. In order to be able to successfully jump, companies need to understand the change of competition in their industry, must nurture a ready supply of talents and close the capability gap between the technology cycles by either external leverage or self-development (Nunes and Breene 2011) (Tse 2015).

While jumping is the process of digital transformation, the gap does define the dimensions of the missing capabilities needed for the new technology cycle.

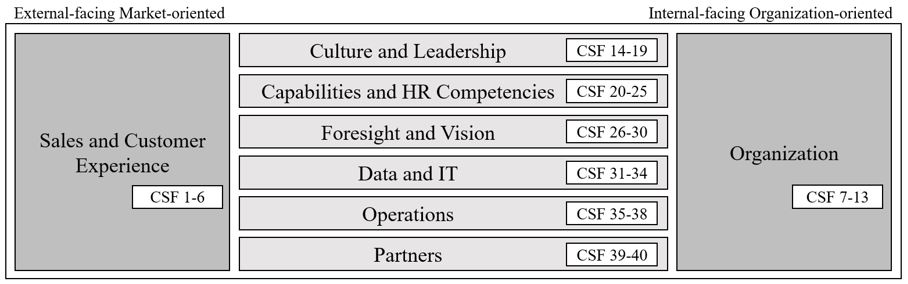

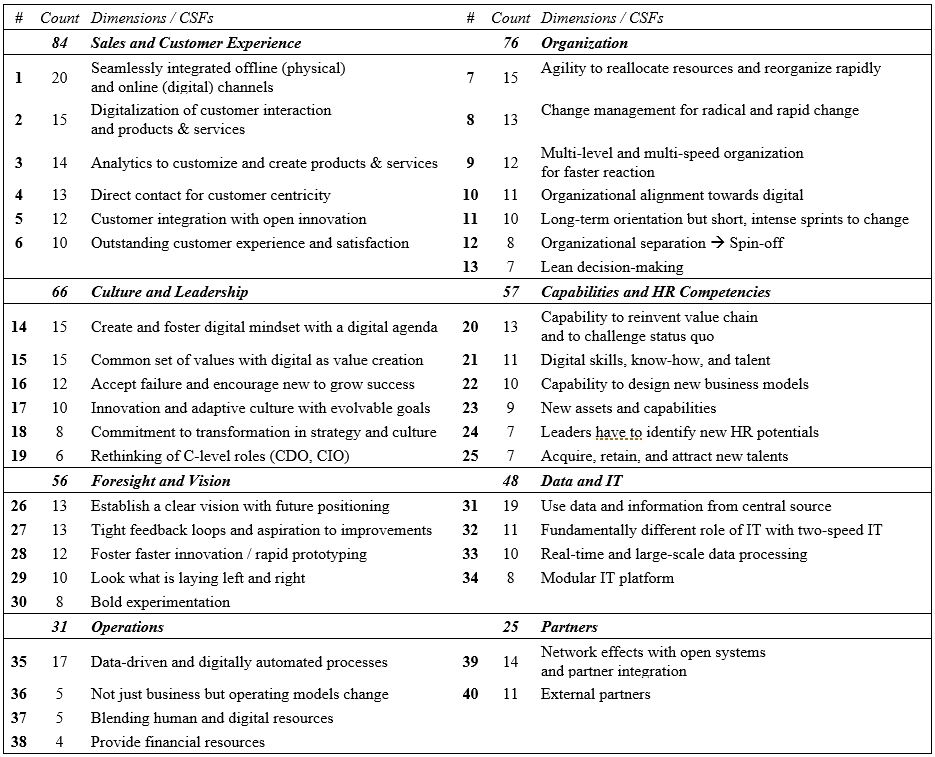

Holotiuk and Beimborn (2017) researched “Critical Success Factors of Digital Business Strategy”. They analyzed 21 relevant industry reports published between January 2011- July 2015, which they found via online search of the terms “digital business strategy”, “digitalization strategy” and variations of it. Among others the documents had been coming from “research centers like MIT Center of Digital Business, research firms like Gartner, technology advisory firms like Accenture or Capgemini, and strategy consultancies such as McKinsey, [Boston Consulting Group] BCG, and Bain” (Holotiuk and Beimborn 2017, 991). The documents had been scanned for their strategic implications, relevance for strategy in general and usefulness to develop a framework. In order to identify and determine information and actions which are most need to reach a defined outcome or goal (Bullen and Rockart 1981), they used the “critical success factor method” (Bullen and Rockart 1981).

As a result Holotiuk and Beimborn (2017) synthesized a framework, consisting of 8 dimensions with clusters of 40 identified critical success factors (CSF). The top two dimensions with the highest counts of critical success factors had been Sales and Customer Experiences and Organization. This reflects also the external market- and society-oriented triggers as well as the internal organization faced motivation.

The top 3 critical success factors are seamlessly integrated (physical) and online (digital) channels (Sales and Customer Experience), use data and information from central source (Data and IT), and data-driven and digitally automated processes (Operations), cf. Table 3.

Seamlessly integrated offline (physical) and online (digital) channels, e.g. China Alibaba´s AI powered Hema stores. Customers on top of the online retail shopping experience can even interact and pay with their mobile apps while they are inside a classical brick-and-mortar-store. The merit is higher offline store efficiency, increased customer loyalty and even more shares in online orders (Biggs, et al. 2017). Augmented reality (AR) also provides customers with a seamless experience by closing the gap between the offline and online touch points (Hilken, et al. 2018). Another aspect of bringing the offline and digital world together is the fact that “Smart Connected Products Are Transforming Competition” (Porter and Heppelmann 2014). And even beyond the sales and customer experience, the Internet of Things (IoT) has today a deep impact on operations by gathering data, analyzing it to optimize production, address customization requirements, generate customer insight and more intelligently manage the business (Sistu 2017).

Use data and information from central source. Porter and Millar said already 1985 (How Information Gives You Competitive Advantage) that the benefits of data and information only exist when they are compatible and that a decentralized design will hinder these possibilities. Part of the challenge is the increase of data and together with multiplied data sources can result from inaccurate data to incorrect filing of compliance information. Centralizing assures access to a common source of trusted data for increased productivity, optimized collaboration and more confident decision making by turning that data into useful business knowledge (Price 2018). But data is also a concern for security and a fundamental rights compliant use and can have negative impacts. Most obvious is privacy and data protection, but also other rights might be affected as poor data quality can prevent fair trials, result in discrimination against women, ethnic minorities and other groups. Data is the basis for AI related technologies like voice assistants, image analysis, search engines, speech and face recognition. Low data quality can come from incomplete data, i.e. the data does not cover what it should cover, and wrong data, i.e. data does not measure, what it should measure (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights 2019). Capgemini says there is no digital transformation without cybersecurity as technologies are vulnerable against outages and access which can lead to the loss of data integrity (Hoorweg and Graaf 2012).

Data-driven and digitally automated processes grow today beyond operations. The next level is intelligent process automation and its five core technologies: (1) Robotic process automation (RPA), (2) smart workflows, (3) Machine learning/advanced analytics, (4) natural language generation (NLG) and, (5) cognitive agents to combine NLG and machine learning to build a completely virtual workforce (Berruti, et al. 2017).

Critical success factors that are missing and which should be considered as part of the building blocks are the downsides or the exponential development of technology

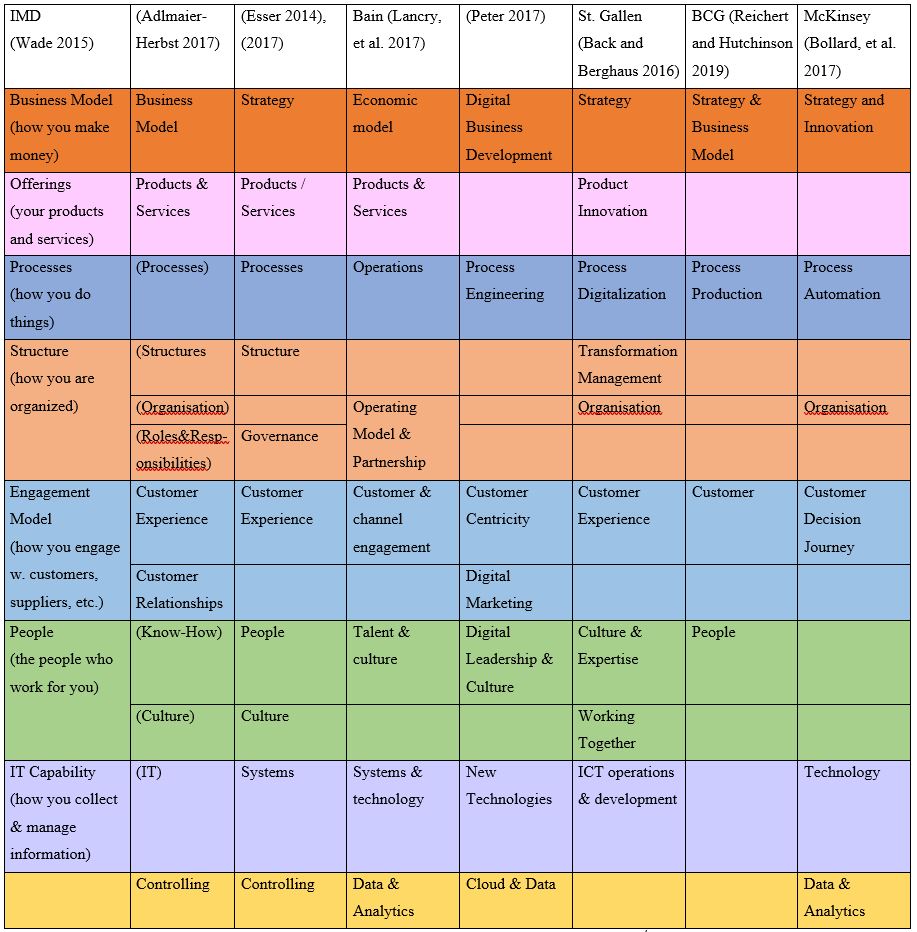

Feichtinger (2018) had a similar approach and compared digitalization frameworks and models to identify building blocks resp. dimensions of the digital strategy.

She synthesized different approaches from Capgemini together with MIT Sloan Management (Westermann, et al. 2011), Cognizant (Corver and Elkhuizen 2014) ,(Wade 2015), (Adlmaier-Herbst 2017), (Esser 2014), (2017), Bain & Company (Lancry, et al. 2017), (Peter 2017), University St. Gallen (Back and Berghaus 2016), BCG (Reichert and Hutchinson 2019), McKinsey & Company (Bollard, et al. 2017) into seven dimensions which are most commonly used (Feichtinger 2018, 50):

- Business model (including the business ecosystem and new markets),

- Products and Services,

- Processes (both internal and customer related processes),

- Customer Experience & Relationships (including e-commerce and customer acquisition),

- Structure & Organization (including governance & transformation management),

- IT & technology (including cloud & data),

- People & Culture (including know-how and leadership).

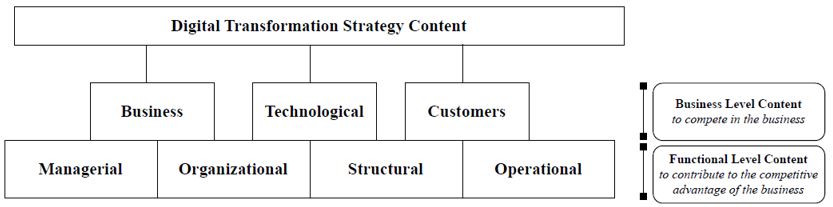

Ismael, Khater and Zaki (2017) synthesized a framework for “Digital Transformation Strategy Content” based on strategic decisions a company is required to do in seven key areas:

- Business (long term objectives, business scope, revenue streams from digitally enhanced products, services and customer interaction)

- Technological (investment decisions; being market follower by adopting already established technologies or market leader by innovating and introducing new technologies)

- Customers (customer experience, changes in the digital enhanced customer journey or products and services integrating physical and digital touchpoints)

- Managerial (financing of the digital transformation; change to innovation and agile working; companies’ digital capabilities and assets for an operational backbone to ensure efficiency and reliability of core operations and for a digital service platform to support business agility and rapid innovations)

- Organizational (decision about employees, culture, talent and skillset; development of a digital mindset and a collaborative work environment supporting employees to adopt quickly to change)

- Structural (internal governance, a strong company-wide coordination along with KPIs ensuring the firm is on the right path to transformation; external collaboration through partnerships or acquisitions and whether new operations will be incorporated into existing structures or new separate units)

- Operational (adaptions to current business processes due to new technology integration; use of data inside processes and decision making to optimize digitally enabled supply chain and interaction with customers)

Ismael, Khater and Zaki (2017) distinguish between business level content to compete in the business and functional level content to contribute to the competitive advantage of the business, cf. Figure 24.

The dimensions that had been identified so far have no focus on any specific industry, especially in manufacturing industries the digitalization of production is a specific strategic topic (Geissbauer, et al. 2018). “Industry 4.0” is a term coming from Germany as part of the high tech strategy 2025 (Wikipedia, Industrie 4.0 2019) meaning the connection of the systems involved in the production flow with software components and internationally also referred to as “cyber-physical systems”, “advanced/smart/digital manufacturing”, “smart factory” or “advanced/smart/digital production/industry” (Wissenschaftliche Dienste 2016). Also, China has a very strong focus on manufacturing industry in digitalization, their strategy is called “Made in China 2025” (MIC2025). This is part of a long-term state regulated strategy for innovation. The predecessor was the “National Medium- and Long-Term Plan for the Development of Science and Technology (2006-2020)” (MLP2020). Made in China 2025 followed the German Industry 4.0 initiative, but goes beyond the state support of innovation, instead planning the complete transformation of the Chinese value chain under the keywords of digitalization and automation (Angbauer and König 2017). The digital model of the USA is based primarily on creative destruction on a global scale with fresh innovative ideas adding competition to established companies, Steiber (2016) calls this “The Silicon Valley Model”.

The described building blocks and dimensions of the digital transformation strategy also have no specific regional characteristic, but we have to take into consideration that the drivers for digitalization are in the USA destructive capitalism focused on disruptive business models with a short-term perspective, in China state regulated focused on industrialization with a long-term perspective and in Europe and Germany technology driven focused on traditional European skills (Arnold 2018).

To sum up what we know about the dimension of digital business transformation strategy:

- We need measurable goals or objectives to determine the financing and investments of the digital transformation and expected revenue streams,

- it affects the company culture as digital transformation is a revolutionary approach where to sacrifice existing ways of competing,

- this demands leadership, as the revolutionary approach and the change of the company culture demands courage, and

- new ways of working and a collaborative work environment to consider the necessity for the fast adoption of the employees to change due to the exponential development of innovations and new technologies.

- New emerging and exponentially developing information technologies are the enablers of digital transformation and there is no digital transformation without cyber-security to ensure accessibility and integrity of data.

- Industry 4.0 is about the operational backbone to ensure efficiency and reliability of core operations especially in production

- Data is the oil that keeps the digitalization running, it need to be collected in a high quality, centrally stored, processed and analyzed. It is the basis for information systems and artificial intelligence and will be used inside processes, for new or digital enhanced business models, products/services and decision making.

- The processes itself have strategic importance as they are the driver of the company value and need to fit seamlessly together.

- People, as human resources are the main drivers of digital transformation, but a digital mindset and new skills and talents must be developed to close the capability gap to deal with new ways of working, innovation and emerging technologies.

- New possibilities in the Customer Relations with digitally enhanced customer journeys and seamlessly integrating the offline and online channels leading to exponentially developing new customer experiences based on

- Products/Service innovations and

- Business model innovations exploiting the opportunities of emerging technologies, data and the changing society.

- With the seamless integration of the physical and digital world inside and outside of the company, the Network and Platform economy as here people, things and businesses have their common touchpoints.

- Europe, China and USA have different approaches towards digital transformation in terms of objectives and perspective of time that makes it worth considering differentiating between different markets.

Works Cited

Adlmaier-Herbst, D. Georg. “Die Bausteine der digitalen Transformation.” KMU Magazin. 08 10, 2017. https://www.kmu-magazin.ch/digitalisierung-transformation/die-bausteine-der-digitalen-transformation (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Angbauer, Christoph, and Thomas König. “Von „Made in China“ zu „Invented in China“ – China auf dem Weg zur Industrie-Supermacht?” In Chinas Innovationsstrategie in der globalen Wissensökonomie, by Joachim Freimuth (eds.) and Monika Schädler, 45-60. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler, 2017.

Arnold, Heinrich. The European Path to Digital Transformation. 10 21, 2018. https://www.theglobalist.com/europe-germany-digitalization-technology-data/ (accessed 08 11, 2019).

Back, Andrea, and Sabine Berghaus. “Digital Maturity & Transformation Studie.” Universität St. Gallen, Institut für Wirtschaftsinformatik. 11 2016. https://aback.iwi.unisg.ch/fileadmin/projects/aback/web/pdf/digitalmaturitymodel_download_v2.0.pdf (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Baghai, Mehrdad, Steve Coley, David White, and Stephen Coley. The Alchemy of Growth: Practical Insight for Building the Enduring Enterprise. Basic Books: New York, 1999.

Berruti, Federico, Graeme Nixon, Giambattista Taglioni, und Rob Whiteman. Intelligent process Automation: The engine at the core of the next-generating operating model . 03 2017. https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/digital-mckinsey/our-insights/intelligent-process-automation-the-engine-at-the-core-of-the-next-generation-operating-model (Zugriff am 05. 08 2019).

Biggs, Chris, et al. How Companies in China Blend Digital and Physical Commerce, The New Retail: Lessons from China for the West. 10 30, 2017. https://www.bcg.com/de-de/publications/2017/retail-technology-companies-china-blend-digital-physical-commerce.aspx (accessed 08 05, 2019).

Blank, Steve. Disruptive Innovations: McKinsey’s Three Horizons Model Defined Innovation for Years. Here’s Why It No Longer Applies. 02 01, 2019. https://hbr.org/2019/02/mckinseys-three-horizons-model-defined-innovation-for-years-heres-why-it-no-longer-applies (accessed 08 04, 2019).

Bollard, Albert, Sanjay Kaniyar, Elixabete Larrea, Alex Singla, and Rohit Sood. The next-generation operating model for the digital world. Report, McKinsey & Company, 2017.

Bullen, Christine V., and John F. Rockart. A Primer on Critical Success Factors. Working Paper No. 1220-81, Boston: MIT, Sloan, 1981.

Christensen, Clayton M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997.

Corver, Quido, and Gerard Elkhuizen. A Framework for Digital Business Transformation. Report, Cognizant, 2014.

Downes, Larry. The Laws of Disruption: Harnessing the New Forces that Govern Life and Business in the Digital Age . New York: Basic Books, 2009.

Downes, Larry, and Paul Nunes. Big Bang Disruption: Strategy in the age of Devastating Innovation . New York: Penguin, 2014.

Downs, Larry, and Chunka Mui. Unleashing the Killer App: Digital Strategies for Market Dominance. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1998.

Esser, Marc R. Chancen und Herausforderungen durch Digitale Transformation. 2014. http://www.strategy-transformation.com/digitale-transformation-verstehen (accessed 08 09, 2019).

—. Digital Maturity Assessment (DMA). 2017. http://www.strategy-transformation.com/digital-maturity-assessment/ (accessed 08 09, 2019).

European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights. Data quality and artificial intelligence – mitigating bias and error to protect fundamental rights. Report, Publications Office of the European Union, 2019.

Feichtinger, Gudula. “Digitalization in SME : a framework to get from strategy to action.” 2018. http://repositum.tuwien.ac.at/urn:nbn:at:at-ubtuw:1-115120 (accessed 08 09, 2018).

Geissbauer, Reinhard, Evelyn Lübben, Stefan Schrauf, and Steve Pillsbury. Global Digital Operations Study 2018. Digital Champions. How industry leaders build integrated operations ecosystems to deliver end-to-end customer solutions. Study, PWC, 2018.

HAN, Zheng. “Session 10 – Business Model.” Marketing Management. Shanghai: Tongji SEM, 03 2019.

Hilken, Tim, et al. “Making omnichannel an augmented reality: the current and future state of the art.” Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, 12 (4), 05 2018: 509-523.

Holotiuk, Friedrich, and Daniel Beimborn. “Critical Success Factors of Digital Business Strategy.” In Proceedings der 13. Internationalen Tagung Wirtschafsinformatik (WI2017), by J. M. Leimeister and W. Brenner (eds.), 991-1005. St. Gallen, Schweiz: Universtität St. Gallen, 2017.

Hoorweg, Erik, and Patrick de Graaf. No digital transformation without cybersecurity. Report, Capgemini Consulting, 2012.

Ismael, Mariam H., Mohamed Khater, and Mohamed Zaki. “Digital Business Transformation: What Do We Know So Far?” University of Cambridge. 11 2017. https://cambridgeservicealliance.eng.cam.ac.uk/resources/Downloads/Monthly%20Papers/2017NovPaper_Mariam.pdf (accessed 07 26, 2019).

Kandermirli, Bahadir Murat. Amazon.com’s Digital Strategies. Case Study Report, The University of Manchester, 2018.

Lancry, Ouriel, Ryan Morrissey, Tom Shannon, Andy Bankert, and Lucy Cummings. Digital Strategy for a B2B World. 02 08, 2017. https://www.bain.com/insights/digital-strategy-for-a-b2b-world (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Nunes, Paul, and Tim Breene. “Reinvent Your Business Before It´s Too Late.” Harvard Business Review, January-February 2011: 80-87.

Peter, Marc K. “KMU Transformation: Als KMU die Digitale Transformation erfolgreich umsetzen.” 2017. https://kmu-transformation.ch/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/FHNW-HSW-Digitale-Transformation-KMU.pdf (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Porter, Michael E. “Strategy and the Internet.” Harvard Business Review, March 2001: 62-78.

Porter, Michael E., and James E. Heppelmann. “How Smart Connected Products Are Transforming Competition.” Harvard Business Review, November 2014: 64-88.

Porter, Michael E., and Victor E. Millar. “How Information Gives You Competitive Advantage.” Harvard Business Review, July-August 1985: 85-103.

Price, Nicholas J. The Benefits of Centralized Data: A Single Source of Information for Your Business Entities. 04 26, 2018. https://insights.diligent.com/data-management/the-benefits-of-centralized-data-a-single-source-of-information-for-your-business-entities/ (accessed 08 05, 2019).

Reichert, Tom, and Rich Hutchinson. The Four Pillars of Digital Transformation. 2019. https://www.bcg.com/de-de/digital-bcg/digital-transformation/overview.aspx (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Schwab, Klaus. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Cologny/Geneva: World Economic Forum , 2016.

Sistu, Phani Bhushan. “Connecting Physical and Digital Worlds to Power the Industrial IoT.” Cognizant. 12 2017. https://www.cognizant.com/whitepapers/connecting-physical-and-digital-worlds-to-power-the-industrial-iot-codex3083.pdf (accessed 08 05, 2019).

Steiber, Annika, and Sverker Alänge. The Silicon Valley Model. Heidelberg: Springer Cham, 2016.

Tse, Edward. China´s Disruptors. New York: Penguin, 2015.

Venkatraman, N. “IT enabled business transformation: From Automation to Business Scope Redefinition.” Sloan Management Review, Winter 1994: 73-87.

Wade, Michael. “Digital Business Transformation.” IMD. 06 2015. https://www.imd.org/uupload/IMD.WebSite/DBT/Digital%20Business%20Transformation%20Framework.pdf (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Westermann, Georg, Claire Calméjane, Didier Bonnet, Patrick Ferraris, and Andrew McAfee. DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION: A ROADMAP FOR BILLION-DOLLAR ORGANIZATIONS. Study, MIT Center for Digital Business and Capgemini Consulting, 2011.

Wikipedia, Industrie 4.0. 06 28, 2019. https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Industrie_4.0 (accessed 07 15, 2019).

Wissenschaftliche Dienste. “Industrie 4.0.” Aktueller Begriff. Deutscher Bundestag, 09 26, 2016.