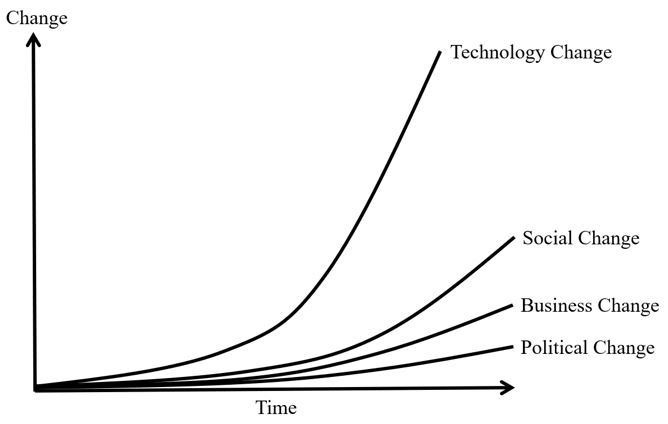

“Born-digital companies”, i.e. companies that are founded on digital platforms and exploiting digital technologies as core components of their business models, have no need for a digital transformation. Unlike “pre-digital” organizations, which are established companies belonging to traditional industries that have been financially successful without digital technologies and capabilities (Tumbas, Berente and Brocke 2017) (Ross, et al. 2016) (Chanais, Myers and Hess 2019). In recent years, these companies have started digital initiatives to explore and exploit the benefits of emerging technologies. The first steps entering digital business models are usually characterized by a high level of uncertainty as this affects products and processes and transforms key business operations as well as organizational structures and management concepts. The digital transformation is very complex and has company-wide impact. The formulation and implementation of a digital transformation strategy has therefor become a key concern for many pre-digital companies and a systematic approach is crucial for success. (Matt, Hess and Benlian 2015) (Hess, et al. 2016).

Getting to a digital transformation strategy has two perspectives. First, the process: how to develop, implement and evaluate the digital transformation strategy considering the new aspects digitalization brings to the organization. Because digital transformation is a continuous effort of high complexity that can reshape a company and its operation, it is important to clearly define and assign roles and responsibilities for the formulation and implementation of a digital transformation strategy. Second, the process of defining a strategy along the dimensions and building blocks of a digital transformation strategy, but this also includes decisions on the necessary resources to be able to execute the strategy and achieve the company goals. (Matt, Hess and Benlian 2015)

Chanais, Mayers and Hess (2019) describe in a case study research 7 main phases of digital transformation formulation and implementation:

- Phase 0: Recognizing the need for digital transformation

- Phase 1: Setting the state

- Phase 2: Initially formulating the digital transformation strategy

- Phase 3: Preparing for the digital transformation strategy implementation

- Phase 4: Starting the digital transformation strategy implementation

- Phase 5: Finding a working mode

- Phase 6: Enhancing the digital transformation strategy

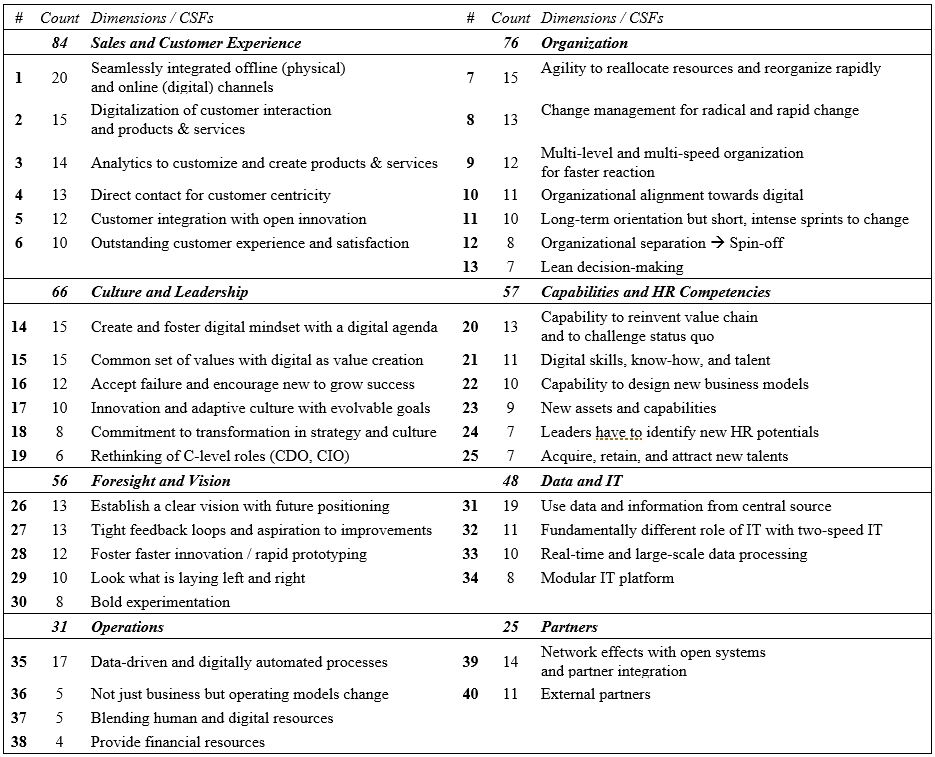

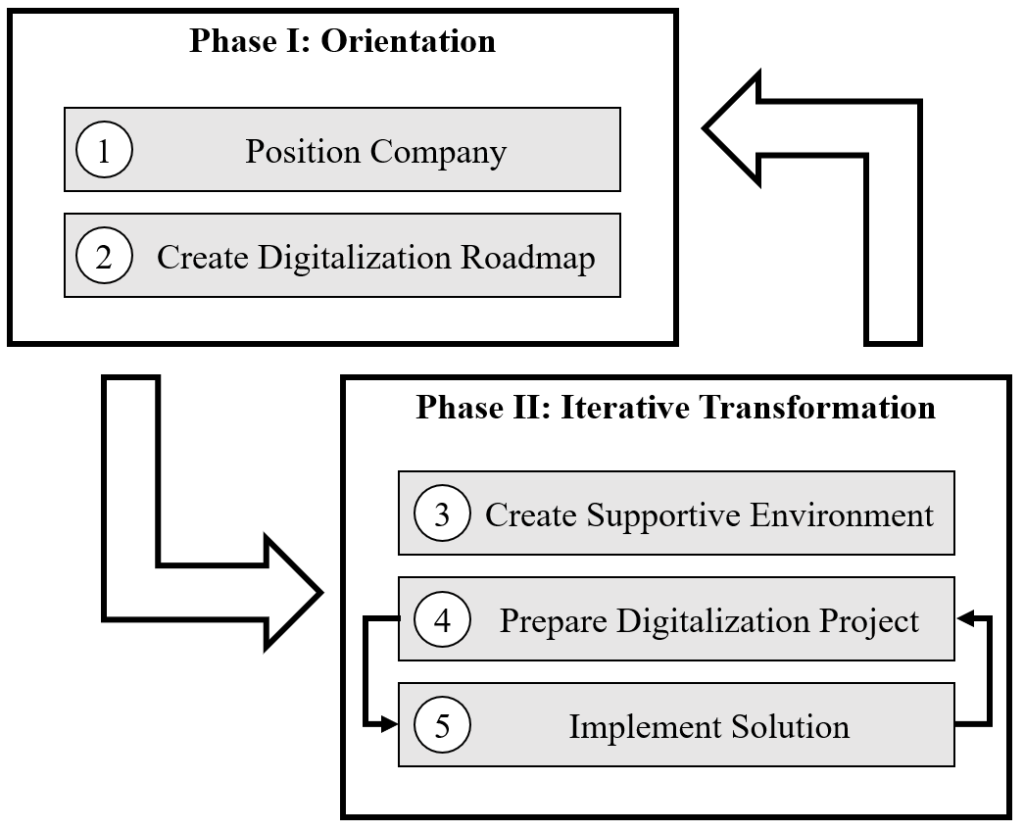

Barann et al. (2019) did a structured literature review of articles from the databases EBSCOHost, ScienceDirect, AISNet and Scopus resulting from the search of keywords in the area of business model innovation, digital transformation, digital innovation, data-driven innovation for SME. They identified requirements for a procedural approach and synthesized these findings into a procedure model for digital transformation in SME, cf. Figure 1.

The following requirements have been the basis for the procedure model: (R1) Integration of external supporter like innovation labs, research institutes and consultancies, (R2) provision of practical orientation based on best-practices, real-life examples and incorporating domain-specific knowledge, (R3) creation of a supportive environment like the awareness of the need for digital transformation which needs to be ensured before any implementation starts, (R4) consideration of tangible goals, i.e. clearly defined and measurable goals, (R5) provision of an individual roadmap, (R6) enabling a stepwise implementation, (R7) identification of opportunities, (R8) assisting reflection & measurement, (R9) balancing strategy and operation, (R10) supporting all levels of digital and data-driven innovation, (R11) consideration of open innovation, i.e. ideas and resources should be shared between internal and external entities, e.g. start-ups. (Barann, et al. 2019)

The synthesized procedure model from Barann et al. (2019) consists of two phases. Phase I is about the formulation of the digital transformation strategy, while phase II is about the implementation.

Phase I, Orientation, has two steps:

- Position company: (a) establish a planning team, (b) understand the business model, (c) analyze the as-is-situation, (d) reviewing digitalization topics, and (e) analyze digital maturity.

- Create digitalization roadmap: (a) generation of ideas, (b) alignment of the ideas with the strategic goals, (c) evaluation of the ideas, and (d) development of a digitalization roadmap.

Phase II, iterative transformation, has three steps:

- Create supportive environment: (a) create awareness, (b) involve employees, and (c) create digitalization culture.

- Prepare digitalization project: (a) select digitalization goal, (b) identify opportunity, (c) select opportunity, (d) perform resource and project planning, and (e) build expertise.

- Implement solution: (a) design solution, (b) refine solution, (c) realize solution, and (d) monitor solution.

Terstegen et al. (2019) researched between July and October 2018 various articles about procedural approaches for the formulation and implementation of a digital transformation strategy with the focus on Industry 4.0 and the manufacturing industry, automotive, electrical engineering, medical devices. They synthesized the identified procedural models into five phases:

- Information Phase, transparency and creation of a common understanding

- Strategy Phase, as-is-analysis, digital vision and strategic direction

- Tactical Phase, determination of targets and deduction of projects

- Operative Phase, implementation of projects

- Controlling, measurement of target achievement

The focus of these procedure models are in three phases of “why” (strategy phase), “what” (tactical phase) and “how” (operative phase), cf. Figure 2.

A detailed overview of the identified procedure models can be found online www.arbeitswissenschaft.net/vorgehensmodelle-digitalisierung (2019).

Feichtinger (2018) also compared various models and identified that they can be aligned into these three major phases:

- Phase 1 (Analysis) asks the question “why” and contains the current status and the analysis phase. The starting points could be a digital maturity assessment (DMA), an evaluation of customer requirements, emerging technologies and industry/market trends.

- Phase 2 (Definition) starts with the question “what”. Here the vision and goals will be defined, the design of the digitalization determined, and the necessary changes deducted.

- Phase 3 (Planning) answers the question “how”. Feichtinger (2018) found out that the third phase is not consistent in the literature. It is not clear whether it is still the planning of the digital transformation or already the implementation as for example this phase had been summarized under operative tasks by Terstegen et al. (2019).

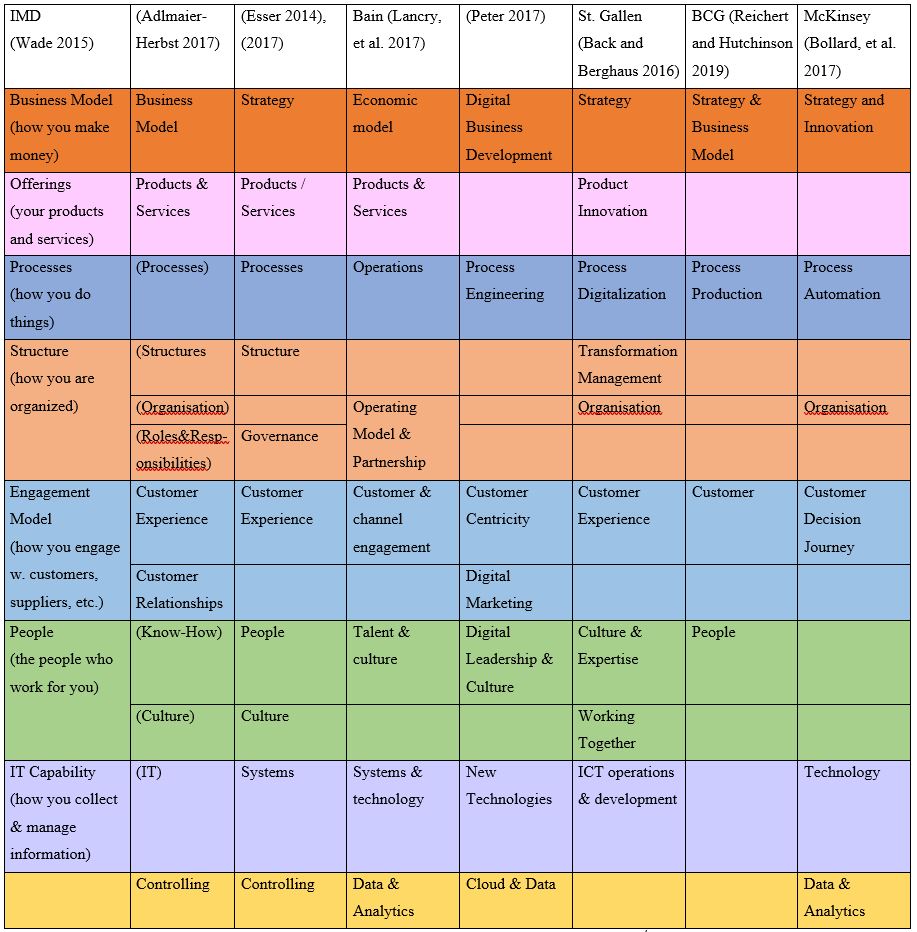

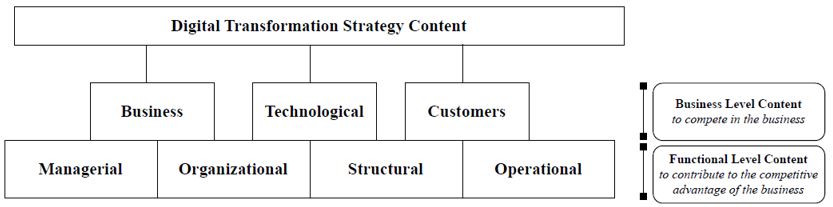

Digital Transformation Strategy has different perspectives and each perspective tries to reach different goals. Matt, Hess and Benlian (2015) speak of four perspectives: use of technologies, changes in value creation, structural changes, and financial aspects. Von Leipzig, et. al. (2017) add to the perspective that the ability to digitally change the value creation is not all about the technology and structural changes, but rather about a radical strategic and cultural change in the organization. The purpose of a digital transformation strategy is to exploit the benefits of emerging technologies to improve productivity, decrease costs and come to innovative products, services and business models. But there is still no coherent alignment in the research where a digital transformation strategy should be allocated (Hess, et al. 2016) (Matt, Hess and Benlian 2015). In analogy to the manufacturing strategy Mills, Platts and Gregory (1995) have given a classification of “strategy” in the business context:

- Corporate Strategy: What set of businesses should we be in?

- Business Strategy: How should we compete in XYZ business?

- Functional Strategy: How can this function contribute to the competitive advantage of the business?

Some argue that a company’s IT strategy can evolve from a functional strategy to a corporate strategy. But IT strategy is about the efficient management of IT infrastructure and applications, where digital transformation strategy incorporates all areas of the organization (Hess, et al. 2016). Sebastian et al. (2017) brings the business strategy and the functional strategy in relation:

- Digital Transformation Strategy: How can we integrate existing business capabilities with new capabilities made possible by emerging technologies?

The characteristic of integrating corporate, business and functional strategies makes it mandatory to align, coordinate and prioritize the many independent dimensions of digital transformation across all other strategies. If these tasks are executed half-heartedly, the formulation and implementation of the digital transformation might lose the scope with possible serious effects on operations. Therefor it is necessary that the person responsible for the digital transformation strategy has enough experience in business transformation and is aligned with the strategy´s targets (Matt, Hess and Benlian 2015).

Singh and Hess (2017) compare the new role of a Chief Digital Officer (CDO), as one option being responsible for the digital transformation, with other existing roles for different levels of strategy within the company, cf. Table 2.

Being responsible for the digital transformation strategy Singh and Hess (2017) identified five skills and competencies necessary: (1) IT Competency, (2) Change Management Skills, (3) Inspiration Skills, (4) Digital Pioneer Skills, and (5) Resilience, which is in “traditional” companies even more important as digital transformation requires profound organizational-wide changes.

Singh and Hess (2017) also identified in their research three different types of roles, Chief Digital Officers play:

- The Entrepreneural Role, with a strong customer focus, exploring IT-enabled innovation and pointing towards a fast-paced technological environment sometimes even with the adoption of whole business models.

- The Digital Evangelist Role, with the focus on inspiring and training people in the organization to prepare them to deal with the challenges and corporate changes in the process of digital transformation.

- The Coordinator Role, with the focus to initiate and design the controlled organizational shift from decoupled silo functions to cross-functional cooperation, which affects many stakeholders of the company on functional (IT, HR), business (marketing & sales, production) and corporate level (executive/advisory board).

It is important to understand that being responsible for the digital transformation strategy does not mean to replace all other strategies and the ones being responsible for them. The company should experiment with emerging technologies and explore the related opportunities across all functional and organizational borders. Therefor being responsible more means acting like a coordinator to ensure collaboration between the different strategic disciplines and that the targets of the digital transformation strategy can be reached with a strong focus on business transformation. (Singh and Hess 2017) (Matt, Hess and Benlian 2015) (Hess, et al. 2016) (Sebastian, et al. 2017)

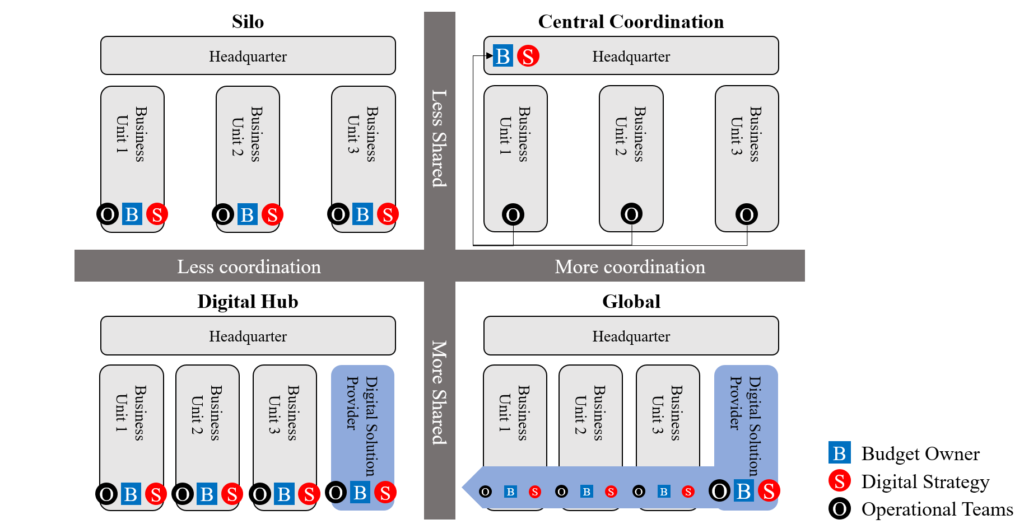

Also, Westermann et al. (2011) come to the conclusion after studying 157 executive-level interviews in 50 companies in 15 countries that the lead for the change need to come from the top, but top level visions seldom leads to bottom-level actions when not supported by top-down communication and governance backed-up by incentives and measurable targets and coordination. They see four different coordination models for digital transformation, cf. Figure 3:

- Silo: No coordination effort as each business unit runs their own digital strategy

- Digital hub: Digital strategy defined by a central digital unit. Each business unit can have their own strategy but must coordinate with the central digital unit to use their solutions and resources.

- Central coordination: Digital strategy defined, funded and coordinated at enterprise level, digital operations developed and managed on business unit level

- Global: Digital strategy allocated to a central digital unit which coordinates strategy and budget. Digital operations are developed and managed on business unit level, but must use solutions and resources coming from the central digital unit

Knowing the procedural aspects and the key participants in the digital transformation strategy, there are several starting points for the transformation journey.

Berman (2012) proposed three different strategic approaches to transformation:

- The “what”: Reshaping the customer value proposition

- The “how”: Reshaping the business model

- Combining both approaches by transforming operating model and customer value proposition at the same time

No organization, even “pre-digital” companies, will start their digital transformation from “zero”. Usually providing information digitally or digital sales channels like e-commerce are existing. Berman (2012) says that “from this starting point, a company’s strategic approach to transformation typically follows one of the three paths”, cf Figure 28.

The paths depend on strategic objectives, industry type, competitive pressure and customer expectations. Companies, who has the business model “Business-to-Business” (B2B), usually start with reshaping operations and then address the customer value proposition to achieve full transformation (Path 1). Companies with the business model “Business-to-Consumer” (B2C), where the focus on the customer value proposition provide immediate benefit, will first focus here and then integrate digital operations (Path 2). Companies seeking industry leadership or companies adding the customer value perspective to their operations (going from B2B to B2B2C) will try to do both at the same time (Path 3). (Berman 2012)

Sebastian et al. (2017) identified in their empirical studies two different types of digital transformation strategies: a customer engagement strategy and a digitized solutions strategy.

“A customer engagement strategy typically aims to create a seamless, omnichannel experience that makes it easy for customers to order, inquire, pay and receive support in a consistent way from any channel at any time” (Sebastian, et al. 2017, 199). It focuses on personalized, innovative and integrative customer experiences. This kind of a strategy is based on collecting customer data and the use of data analytics to better understand and anticipate customer demands.

“A digitized solutions strategy aims to reformulate a company’s value proposition by integrating a combination of products, services and data” (Sebastian, et al. 2017, 199). It is driven by R&D to create digital products and services by combining existing capabilities with digital capabilities. This may result in the shift from selling a product to offering services with the effect of recurring revenues like Porter describes it in “how smart connected products are transforming competition”. (Porter and Heppelmann 2014)

Kaltenecker, Hess and Huesig (2015) researched the effect of shifting from product-selling to service offerings on the example of the software industry changing from selling licences for on-premise usage to offering their software on-demand out of the cloud. Their assumptions are based on the “Innovator’s Dilemma” (Christensen 1997), as well-established companies are facing this dilemma when they hold on to their technologies, even though emerging technologies with a potential of disruption are already available in the market. Kaltenecker, Hess and Huesing (2015) summarized different management strategies adopted by the software industry to prevent potential disruption using the example of shifting towards offering software-as-a-service out of the cloud, cf Table 3.

The media industry faced already the digital disruption as the digital change is undeniable when the customers shift from buying a newspaper to opening a news app, from renting a DVD to online streaming, from buying a cookbook to getting customized recipes onto the smartphone (World Economic Forum 2019). Hess et al. (2016) researched media companies and their digital transformation strategies. As a result, they suggested guidelines for formulating a digital transformation strategy based on four aspects where key strategic decisions have to be made, cf Table 4 : (1) use of technology, (2) changes in value creation, (3) structural changes, and (4) financial aspects.

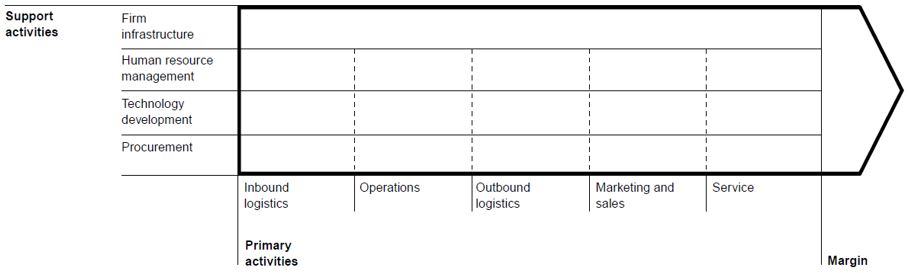

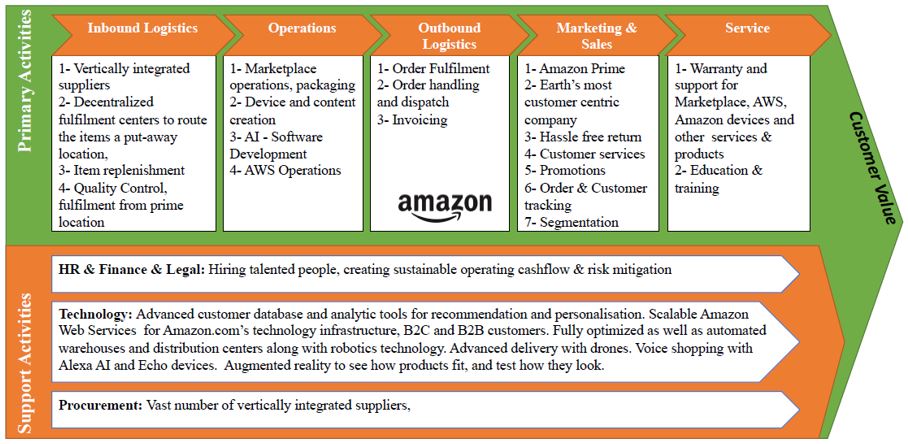

While the use of technology, structural changes and financial aspects are not necessarily industry specific, the value creation is different in each industry. To get also to an industry specific formulation of the value creation, Porter proposed to define the strategy along the value chain (Porter and Millar 1985) (Porter 2001).

Bughin and Zeebroeck (2017) identified besides disruption a second challenge in the transformation of the value creation: Based on their survey of 2000 incumbent companies across all major industries and countries, they see that for the majority digital initiatives show only little effect. On the other side top-performing companies could achieve up to 80 percent higher revenues than the industry average and achieve a digital return on investment (ROI) that is 10 times higher than the above mentioned low-performing companies in their survey. The outperformer usually had offensive strategies, i.e. commitment to radical changes, e.g. willingness to cannibalize their current revenues and to invest into digital technology. Bughin and Zeebroeck (2017) classified the digital strategies found into six types, where the first three are primarily offensive and the second three defensive, i.e. meant only to improve the existing operating models, cf. Table 5.

As a summary, the formulation and implementation of a digital transformation strategy demand huge efforts as all strategic areas of the company are related and it takes a revolutionary approach for fundamentally changes. The leading must come from top, but the difficulty is to bring the visions and goals to the bottom. Therefore being responsible for the digital transformation is the role of a coordinator across the organization with experiences in business transformation. The formulation of the strategy has four aspects: use of technology, structural changes, financial aspects and especially changes in the value creation. There are differences in the transformation journey, type and management of the digital transformation strategy depending on industry type, business model and boldness of the company, i.e. whether to choose an offensive or defensive strategy. To answer the question how to formulate and implement the digital transformation strategy, there are at least three core phases: Analysis, Definition and Planning.

Works Cited

Adlmaier-Herbst, D. Georg. “Die Bausteine der digitalen Transformation.” KMU Magazin. 08 10, 2017. https://www.kmu-magazin.ch/digitalisierung-transformation/die-bausteine-der-digitalen-transformation (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Barann, Benjamin, Andreas Hermann, Ann-Kristin Cordes, and Friedrich Chasin. “Supporting Digital Transformation in Small and Medium-sized Enterprises: A Procedure Model Involving Publicly Funded Support Units.” Proceedings of the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Science. Grand Wailea, Maui: University of Hawaii at Manoa, Shidler College of Business, 2019. 4977-4986.

Berman, Saul J. “Digital Transformation: opportunities to create new business models .” Strategy & Leadership, 40 (2), 2012: 16-24.

Bollard, Albert, Sanjay Kaniyar, Elixabete Larrea, Alex Singla, and Rohit Sood. The next-generation operating model for the digital world. Report, McKinsey & Company, 2017.

Bughin, Jacques, and Nicholas Van Zeebroeck. 6 Digital Strategies, and Why Some Work Better than Others. 07 31, 2017. https://hbr.org/2017/07/6-digital-strategies-and-why-some-work-better-than-others (accessed 08 19, 2019).

Chanais, Simon, Michael D. Myers, and Thomas Hess. “Digital transformation strategy making in pre-digital organizations: The case of a financial service provider .” Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 28 (1), 03 2019: 17-33.

Christensen, Clayton M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 1997.

Esser, Marc R. Chancen und Herausforderungen durch Digitale Transformation. 2014. http://www.strategy-transformation.com/digitale-transformation-verstehen/ (accessed 08 09, 2019).

—. Digital Maturity Assessment (DMA). 2017. http://www.strategy-transformation.com/digital-maturity-assessment/ (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Feichtinger, Gudula. “Digitalization in SME : a framework to get from strategy to action.” 2018. http://repositum.tuwien.ac.at/urn:nbn:at:at-ubtuw:1-115120 (accessed 08 09, 2018).

Hess, Thomas, Christian Matt, Alexander Benlian, und Florian Wiesböck. „Options for Formulating a Digital Transformation Strategy.“ MIS Quarterly Executive, 06 2016: 123-139.

Kaltenecker, Natalie, Thomas Hess, and Stefan Huesig. “Managing potentially disruptive innovations in software companies: Transforming from On-premise to the On-demand.” The Journal of Strategic Information Systems, Vol. 24 (4), 12 2015: 234-250.

Lancry, Ouriel, Ryan Morrissey, Tom Shannon, Andy Bankert, and Lucy Cummings. Digital Strategy for a B2B World. 02 08, 2017. https://www.bain.com/insights/digital-strategy-for-a-b2b-world (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Matt, Christian, Thomas Hess, and Alexander Benlian. “Digital Transformation Strategies.” Business & Information Systems Engineering, 05 14, 2015: 339-343.

Mills, John, Ken Platts, and Mike Gregory. “A framework for the design ofmanufacturing strategyprocesses: a contigency approach.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 15 (4), 1995: 17-49.

Peter, Marc K. “KMU Transformation: Als KMU die Digitale Transformation erfolgreich umsetzen.” 2017. https://kmu-transformation.ch/wp/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/FHNW-HSW-Digitale-Transformation-KMU.pdf (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Porter, Michael E. “Strategy and the Internet.” Harvard Business Review, March 2001: 62-78.

Porter, Michael E., and James E. Heppelmann. “How Smart Connected Products Are Transforming Competition.” Harvard Business Review, November 2014: 64-88.

Porter, Michael E., and Victor E. Millar. “How Information Gives You Competitive Advantage.” Harvard Business Review, July-August 1985: 85-103.

Ross, Jeanne W., Ina M. Sebastian, Cynthia Beath, Martin Mocker, Kate G. Moloney, and Nils O. Fonstadt. “Designing and Executing Digital Strategies.” Thirty Seventh International Conference on Information Systems. Dublin: Association of Information Systems, 2016. 1-17.

Schallmo, Daniel R. A., and Christopher A. Williams. “Roadmap for the Digital Transformation of Business Models.” In Digital Transformation Now! Guiding the Successful Digitalization of Your Business Model, by Daniel R. A. Schallmo and Christopher A. Williams, 41-68. Cham: Springer, 2018.

Sebastian, Ina M., Martin Mocker, Jeanne W. Ross, Kate G. Moloney, Cynthia Beath, and Nils O. Fonstad. “How Big Old Companies Navigate Digital Transformation.” MIS Quarterly Executive, 09 2017: 197-213.

Singh, Anna, and Thomas Hess. “How Chief Digital Officers Promote the Digital Transformation of their Companies.” MIS Quarterly Executive, 03 2017: 31-44.

Terstegen, Sebastian, Simon Hennegriff, Holger Dander, and Patrick Adler. “Vergleichsstudie über Vorgehensmodelle zur Einführung und Umsetzung von Digitalisierungsmaßnahmen in der produzierenden Industrie.” Bericht zum 65. Arbeitswissenschaftlichen Kongress vom 27. Februar – 1. März 2019. Dortmund: GfA Press, Gesellschaft für Arbeitswissenschaften e.V., 2019. C.3.13, 1-6.

—. Vorgehensmodelle zur Einführung und Umsetzung von Digitalisierungsmaßnahmen in der produzierenden Industrie. 02 27, 2019. https://www.arbeitswissenschaft.net/vorgehensmodelle-digitalisierung (accessed 08 17, 2019).

Tumbas, Sanja, Nicholas Berente, and Jan vom Brocke. “Born Digital: Growth Trajectories of Entrepreneural Organizations Spanning Institutional Fields.” Thirty Eighth International Conference on Information Systems. South Korea: Association of Information Systems, 2017. 1-20.

Von Leipzig, T., et al. “Initialising customer-orientated digital transformationin enterprises.” Procedia Manufacturing, 8, 2017: 517-524.

Wade, Michael. “Digital Business Transformation.” IMD. 06 2015. https://www.imd.org/uupload/IMD.WebSite/DBT/Digital%20Business%20Transformation%20Framework.pdf (accessed 08 09, 2019).

Westermann, Georg, Claire Calméjane, Didier Bonnet, Patrick Ferraris, and Andrew McAfee. DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION: A ROADMAP FOR BILLION-DOLLAR ORGANIZATIONS. Study, MIT Center for Digital Business and Capgemini Consulting, 2011.

World Economic Forum. Four digital trends reshaping the media industry. 2019. http://reports.weforum.org/digital-transformation/digital-trends-in-the-media-industry/ (accessed 08 19, 2019).